Living Under The Hunter’s Moon.

Tracey Emin

White Cube MasonsYard

Exhibition Review

Written December 2020.

whitecube.com

Every Single Thing changed because of You - Because The sky is the sea (2020) © Tracey Emin. All rights reserved, DACS 2020. Photo © White Cube (Ollie Hammick)

Every Single Thing changed because of You - Because The sky is the sea (2020) © Tracey Emin. All rights reserved, DACS 2020. Photo © White Cube (Ollie Hammick)If there’s one gallery that for me makes maintaining any sort of moral stand against the institution of elite art a futile act, it would have to be White Cube— consistently engrossing and profound displays of work are hard to keep away from it turns out, this time by way of one of the most divisive, yet important artists to have emerged not only from the YBA’s but from Britain itself: Tracey Emin. What I knew about Emin’s work before visiting her solo show A Fortnight of Tears at White Cube Bermondsey back in 2019 (twice, no less) was based mainly on here-say, the odd online article and a much loved second-hand book on Sarah Lucas (picked up from a second-hand shop in Blackfriars). It was through those exhibit visits however, that I was able to absolutely fall in love with the straight-talking, obsessive and narcissistic creative behemoth with her regularly vilified, consistently unsettling and notoriously unapologetic work, along with it, everything that she represents as a woman who’s battled demon after demon, baring her scars for the world to see. There, much like the exhibition in question, Living Under The Hunter’s Moon, was a hypnotic, crushing, disturbing and unsettling sense of what it means to be alive, not only from her own perspective but generally, in a way only that was only magnified and made more poignant by the sheer scale of her output, the powerful omittance of any censorship whatsoever and a mastered fluidity across mediums, the list of which impressively, immodestly and almost impossibly lengthy.

With this in mind, Living Under The Hunter's Moon at White Cube Mason’s Yard (the smaller, slicker and succinct sibling of Bermondsey) was something that I had to experience in the flesh, regardless of social distancing, pandemic-paranoia or a dangerously dwindling bank account (the trip costing £8.50 was definately a factor in me even writing this). Much like its predecessor, Living Under The Hunter's Moon features an ensemble of works across paint, bronze, moving-image and neon. Given the half-familiar selection of works and compact size (as big as Mason’s Yard would allow), the exhibit at first glance felt as if an addendum, an appendix or a pairing to AFOT, especially with the ground floor opening with paintings; her truest self in its rawest, most primal form, and a central bronze piece: There Was So Much More of Me, (2019), both of which amongst the most memorable mediums in AFOT. Most if not all of her paintings are rooted in abstraction (if such a word could do them justice), both primal and destructive. Reclining or vulnerably exposed nude bodies are often made up of hurried, frantic and violent strokes that sometimes look as though the task was the vindictive vandalism of subjects rather than the creation of them.

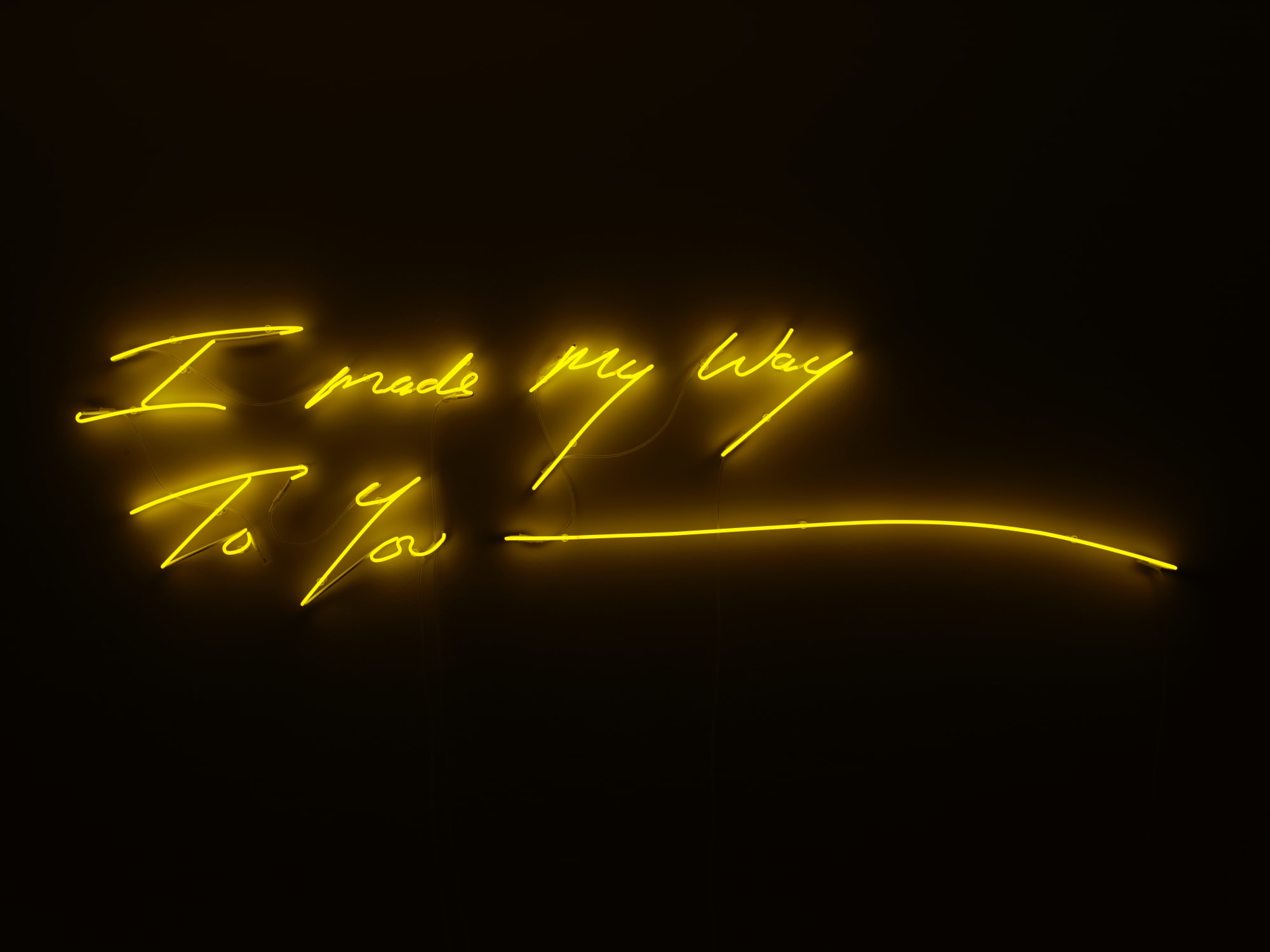

I Made My Way To You (2020), © Tracey Emin. All rights reserved, DACS 2020. Photo © White Cube (Ollie Hammick)

Titles such as Every Single Thing changed because of You - Because The sky is the sea (2020) and Only room in my mind For you (2019) allude, as do many of her works, to an unknown central muse, the source of her cathartic emotional outpour. The two paintings in particular, similar both in dimensions and in scarce canvas completion, seemed to have their creative energy centred on the removal of faces— a damnatio memoriae of sorts, controlling the narrative in a way that salvages the little remains of anonymity available, especially with titles both so revealing and exposing. Just as with AFOT, Emin included a bronze piece (created in an edition of three, if you can believe it)— at nearly a hundred inches long, There Was So Much More Of Me (2019) has nothing on the other worldly relic sized versions featured at AFOT, but assuming a similar position of subservience and exposure, it speaks a sexual vulnerability, arguably more explicit than any other work in the show.

The eponymous painting, The Hunters Moon (2020) was the most unsettling of the lot— from its jaunty, capitalised, scruffy words, to its sole use of a deep red (no doubt alluding to the Blood Moon alias given to the moon in its Hunter phase), playing with negative space by presenting what looks like two subjects in an embrace with a red background, their forms staggered, faint at times without distraction or visual interruption. As for This Was The Beginning (2020) and Total Fucking Desperation (2020), they seem not only in title but also in appearance to be the polar opposites of one another; perhaps representations of the respective start and the end of a period of time in Emin’s life, began with optimism and ending in carnal frustration. Despite its scale and the way in which the canvas has been worked, the former is a surprisingly calming painting; a feeling aided by daubings of white that not only give the figure life but also contrasts gently with the blue and the canvas’ colour natural hue itself, allowed to drip and trail as if thin, melted ice cream. If The Hunters Moon wins at unsettling, then Total Fucking Desperation wins at being straight-up disturbing— destructive energy can be read in everything from the hurried and ungentle thick brush strokes that quite literally smother the canvas with deep black and blue, to the title itself. Interestingly, it seems to be the only painting that was started with red, as opposed to it appearing in later, as a secondary, tertiary or other layer later in the painting’s development.

There was so much more of me (2019) © Tracey Emin. All rights reserved, DACS 2020. Photo © White Cube (Theo Christelis)

It’s worth mentioning that as I arrived, and was signing in with the masked invigilator and her iPad, the eerie, throaty screams of a female voice, sounded from the chamber in the gallery below us all. With no-one batting an eye-lid, I was pretty sure that I was in for some peculiar performative intensity and I wasn’t wrong. Stepping down into the basement level of the gallery, Homage To Edvard Munch And All My Dead Children (1998), a two minute ten seconds long, super-8 filmed moving-image piece was being projected onto the farthest wall. Standing amongst two other visitors (one of which was told off by security for stooping) I took in the nostalgic, off-kilter colour palette and the soft lapping of waves, ebbing and flowing. Ninety percent of the piece was actually quite relaxing; forgetting the foetal positioned faceless subject (assumed to be Emin) on a wooden pier, the hypnotic waves, especially with the scale and dynamism of the audio provided a perfect escape from the chaos of the world above. The other ten percent— screaming. It came without warning, shrill and intense with a rattling timbre. Emin’s connections with Munch are well documented (here, not only with Norway as the location, but also potentially with the scream echoing his most famous painting?) but the dead children part— a reference to the aborted child (and possibly another) referenced throughout her works? Even the press release provided no real clues. Yet, I watched the piece, sadistically, a good four or so times before moving on. Following COVID-friendly floor-arrows round to the cubby containing her neon piece I Made My Way To You (2020) and a maquette of The Mother (2020), a real sense of pause and respite was offered— the yellow from the neon, and the minute size of the small bronze figure both strangely reflecting and calming, despite the vein of pain, suffering and loss that they were both created in (The Mother is a sculpture of Emin’s mother in her eighties, who has since died).

Living Under The Hunter’s Moon— a succinct, sanguine-slathered journey across loss and sadness, true to the Emin that so many love and hate. Even as I walked around the exhibition, the more I said the title to myself, the more the more it felt like a personal declaration than simply a title, almost as though Emin herself feels as though she is the quarry beneath the moon to be pursued, or rather the assailant who shall be pursuing the victim. In any case, the exhibition was something— not necessarily covering new ground in theme, medium or curation, and nowhere as emotionally draining as A Fortnight Of Tears (which given the year that’s unfolded, isn’t necessarily a bad thing) but in some ways, almost equally compelling, memorable and fascinating. I couldn’t help but think as I perused the works— one, of how her work, out of the context of a multi-million pound gallery, could be very easily attributed to someone genuinely mad; a genuinely troubled soul, but also how madness is often a conduit to greatness (cue Dali, Sun Ra, Van Gogh...) and how, in some ways, we are all a little mad in the face of what life throws at us. Abortion, rape, death, rejection, depression, isolation, guilt, abuse, sorrow and mourning— these are things that will affect many, if not all of us in some way, shape or form; Emin here is just speaking, or rather working, aloud with it all. Even as an artist myself, the idea of having the vast majority of my career dedicated to trauma— especially my own trauma, seems quite a depressing one. Yet what braver, or better way is there to take on the very things that damage and ruin so many lives, than to immortalise them with ferocity, fearlessness and form for all to see— big, proud and as loudly as possible? It does beg the question however— at what point can the catharsis of emotional creative output become so addictive that not sharing becomes harder than sharing, and by immortalising yourself through such life-changing events over and over, do you ever really get to let go of them?