© Dawoud Bey. ‘Two Girls from a Marching Band’, Harlem, NY 1990, from Street Portraits (MACK, 2021). Courtesy the artist and MACK.

If pre-internet photography has taught us anything, it is that palpability is integral to artistic authenticity; that mastery can make itself known in the most simple of approaches. In the case of New York-native photographer and educator Dawoud Bey, who has spent the majority of his career chronicling the black experience within his works, it is these very factors that make his series ‘Street Portraits’ as compelling as it is: simple, black & white large-format polaroid portraits, collectively serving as a testament to process, to pride and their combined power. The eponymous monograph, published by MACK books, features over seventy portraits created across a three year period between 1988 and 1991 in a range of american cities such as Brooklyn, Harlem and Rochester. What Bey embarked upon was not a simple documentation of people that simply shared his ethnicity, but rather a collaborative examination of what it was to be black, not only photographing subjects but also gifting sitters with a copy of the physical result. Just as Kerry James Marshall or Henry Taylor did with paint, Bey presented a reimagining of blackness, by presenting it within the vein of the everyday; vulnerability, sensitivity and delicacy amongst other things remaining key themes throughout the series, with each challenging the weight of preconception and stereotype that many black people the world over had to, and continue to, navigate and challenge.

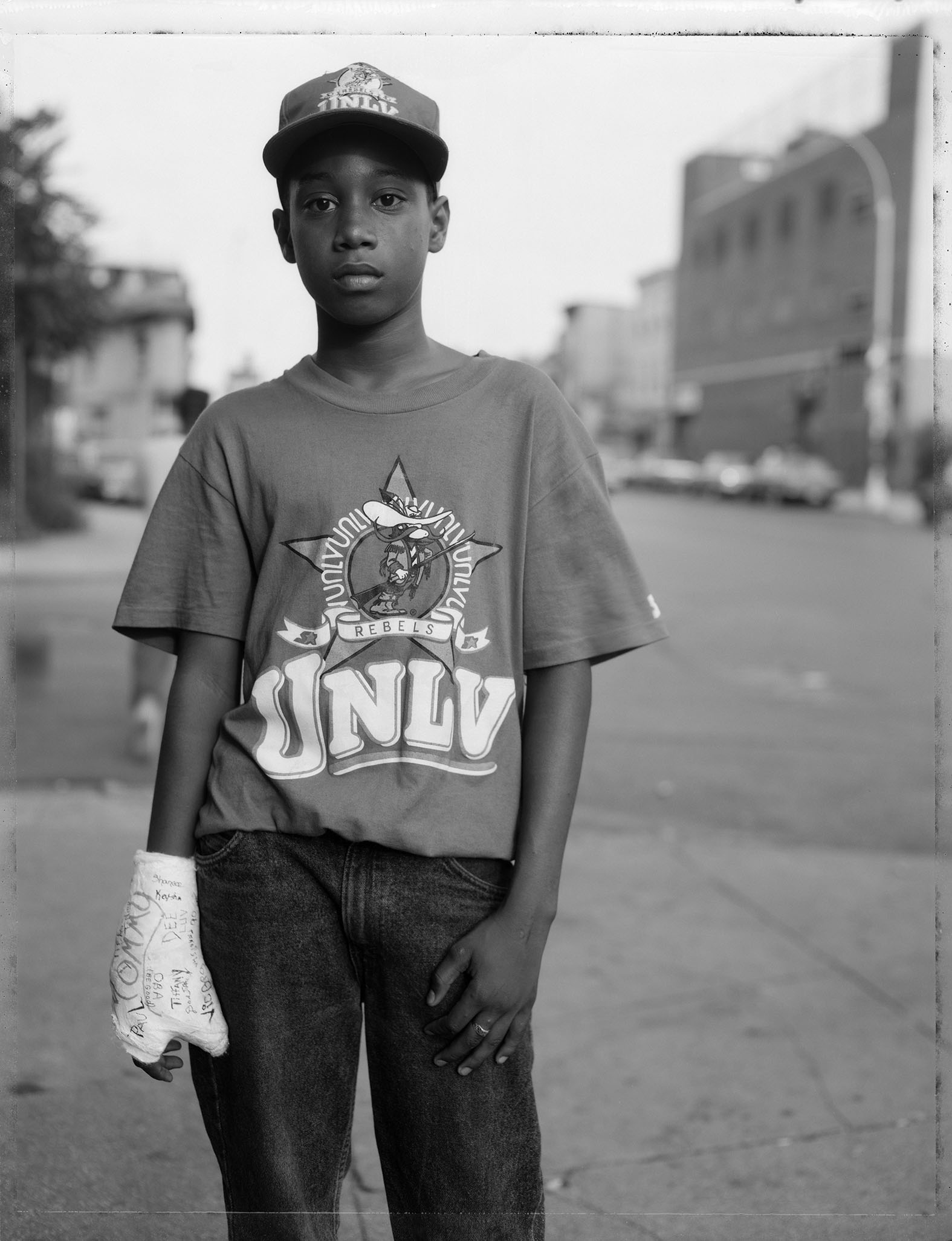

© Dawoud Bey. ‘A Boy with a Cast’, Brooklyn, NY 1988, from Street Portraits (MACK, 2021). Courtesy the artist and MACK.

The lack of colour in the images emphasises with a timelessness away from the bias of the colour processing of old, allowing each subject to unequivocally belong within their surroundings, galvanised by an undeniable depth and artistic drama by way of the large format itself. The range and variety in the framing of images helps to animate his subjects, giving gentle tells to Bey’s artistic process, while working against the historical grain of ethnographic black documentation, famously reliant on reductionistic uniformity. The breadth of the subjects themselves— the elderly, middle-aged couples, adolescents and children, help paint vivid worlds in which community is not only present, but integral to collective identities, showing the nuances of local and endemic cultures along the way. We are given an insight into the sartorial trends, hairstyles, vocations, pastimes and lifestyles of these strangers— parents, siblings, grandparents and other relatives, with each, especially now after thirty years, seeming even more special from the perspective of both cultural preservation and nostalgia; the faint markings from the polaroid lm itself bordering many of the photos, reiterating the delicacy of looking into the past by way of tangible, original artefacts. As a publication itself, ‘Street Portraits’ is one to behold. Donning a print either side of its cloth cover and spanning across just over a hundred pages, there’s an endearing, near cinematic sense of journey in its unfolding, one that apt dimensions help make one worth savouring. The image titles, largely understated, factual and anonymous, seem a subtle nod to both european and american art history, in which subjects often gave so much of themselves within a painting, retaining only their names. The accompanying essay (Dawoud Bey: Griot with a camera), written by musician and writer Greg Tate, although at times informative, at others, full of cultural passion, quotes and poetic wordplay, digresses far too often (and convolutedly) from the series itself, ultimately missing out on a key chance to provide a focused commentary crafted in the same vein as the direct, stoic and gentle images themselves. Yet, despite this, and the somewhat vulnerable outer fabric of the monograph’s cover, little else is able to take away from the overall success of ‘Street Portraits’ in design, curation and content.

© Dawoud Bey. ‘A Girl with a Knife Nosepin’, Brooklyn, NY 1990, from Street Portraits (MACK, 2021). Courtesy the artist and MACK.

Whether it’s the well-wished scrawls of names on a young boy’s cast-clad hand in ‘A Boy with a Cast’, the expletive badges on a young man’s jacket in ‘A young MC with buttons’ or the large, ornate earrings of a woman mid-embrace in ‘A couple in Prospect Park’, it is these ner details which help accentuate the profound narrative in the images within. Some subjects pose with an air of apprehension; others smile softly and proudly, but in each and every photograph, there’s the feeling that they too know the importance not only of the series itself, but of their place within it. ‘Street Portraits’ illuminates as much as it illustrates, humors as much as it honors and narrates as much as it navigates: a sincere, quintessential take on the black experience, that goes beyond the casual snapshot to tell life stories of community, personality and identity, transcending trend and time.