I could’ve made that! —

Musings on the value of art.

Essay

Published February 2021.

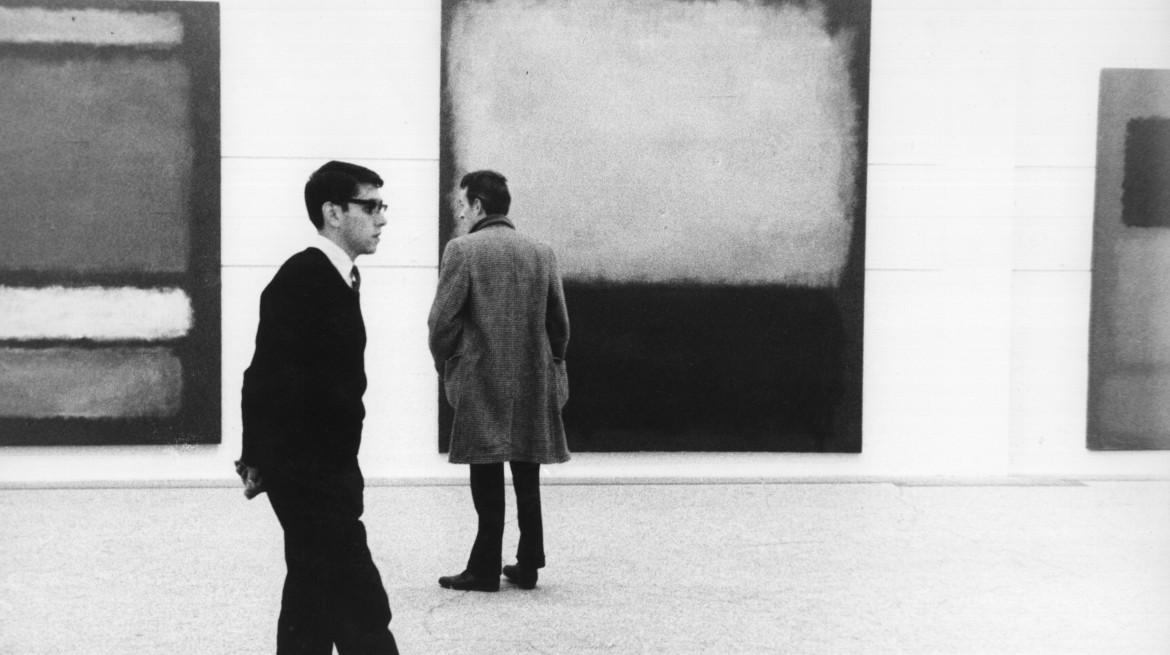

Photo © Whitechapel Gallery (Rothko in Britain).

From the likes of the bootleg Supreme skateboard (made by simply screwing skate trucks into an painter’s palette) that sold at auction for $20,000, to the collosal Rhein II by Andreas Gursky which went for an easy $4.3 million, the real art world, of auction houses, private buyers, storage facilities and fancy dinners is one in which the super rich are able to make headlines with ease, making purchases that defy the financial logic, restraint and understanding of the vast majority of society, all in the name of investment, appreciation and ultimately, fun. So when I saw Netflix’s newest documentary— Made you look: a true story about fake art advertise I was intrigued, not only in finding out about the person behind the forgeries, but also in seeing how value surrounded art that was, essentially worthless. Although not the most dramatic documentary spawned by the streaming site, and perhaps (at least for me, some fast-paced dialogue moments that required some rewinding) there were plenty of draw-dropping moments, curious twists and turns in the events leading up to, and during, what was the largest case of art fraud in the United States. The work in question, a forgery of abstract impressionist Mark Rothko— a piece, Untitled 1956, created by Chinese street artist and maths professor Pei-shen Qian (hired by Long Island art dealer Glafira Rosales, by way of her boyfriend Jesus Angel Bergantinos Diaz by way of the now closed art dealer Knoedler— you can read all about it by clicking here), was sold for $8.3 million to Italian businessman Domineco de sole. The documentary itself made for decent Saturday afternoon viewing, especially in wondering just how culpable Knoedler and their former dealer, Ann Freedman were in the whole situation, as well as the irony in Pei-Shen himself being let off the hook, having returned to China before the trial, despite him being the creator of the actual art that caused the whole situation. Interestingly however, the documentary didn’t seem to break the forth wall of the whole dramatic chain of events, touching on the wider, almost deafening question that rang throughout the whole show. If several art experts (including seasoned art dealer Ann Freedman, an actual Rothko expert— David Anfam and to some degree, Rothko’s own son Christopher) can be deceived so greatly by the work of a forger— work that sold for nearly ten million dollars, mesmerized so many audiences and yet became worthless overnight, then what does that say about the true nature of value in art at large?

The situation concerning Knoedler and Freedman was embarrassing to say the least and devastating most parties, in terms of finance, reputation and trust. Yet, there is a strange, perhaps perverse glimmer of humour in the whole thing. Is the humour primarily in the fact that an expert who had dedicated his entire life to specific artist, could still be hoodwinked by a regular joe who happens to be good at painting? Is it in the fact that art collectors and buyers themselves, who confessed to things like falling in love with the painting (direct quote from Freedman) or describing it as sublime (direct quote from Swiss Art Dealer, Ernst Beyeler), can generate such strong emotions about something which is categorically inauthentic? Or is it in the fact that buyers will happily part with amounts of money that the average person in their respective countries would not make in three lifetimes of work, for a painting, the raw materials of which probably cost a few grand to make? Personally, I think, all of the above. As an inside-outsider like myself, the idea of paying $8.3 million for a real Rothko is just as mind-bending as paying for a forgery. Yet, there still remains the existential conundrum of value. The more I thought about it, the more it seemed as though all art is worthless at its core (—depending on how much you want to unravel that statement, you could go as far as saying all objects are at their essence, worthless, but that’s another story) and all value is subjective. In the art world however, that subjectivity is lead by the person who can bid the highest, with the rest of the world following suit. It may be, for example, just be a painting of a flower by some art school student, but if a bidder puts down a $3 million bid on it, then that’s what it’s worth. That being the case, then perhaps there is an argument in suggesting that forgeries— sublime forgeries are in theory equally as valuable as their originals. Rightly or wrongly, are able to generate all of the feelings, emotions and experiences associated with their original versions: pride, power, seduction, transcendence or admiration. They convince many experts, they often stimulate the ageing process which they should have undergone if real and they require a near identical amount of skill needed to make the original. Their ideas are not always original (the one at the heart of the court case was not a replica, but an assumed lost, original painting), but they’re able to capture the true essence of the artist. Forgeries are placebos that despite being worthless in art world terms, serve the purpose of that which they emulate: to be admired by those rich enough to afford the exclusivity to such a right. It is no secret that much of the value of art in lies in the experience that art gives. If nothing else, the documentary drove home the very glaring reality that art— real art, of the real art world is governed by and dependent on a series of complex factors within human and social psychology, than any universally understood rationale, empiricism or logic. Though a little abstract a thought, it almost seems as though the art world itself operates just like a pretentious conceptual work of art: incredibly large, complex and impressive, yet cannot be understood without a never-ending, convoluted appendix filled with rules, references and footnotes, often baffling even those involved in it— the buyers, investors or collectors, all merely performers competing with one another for inanimate, and largely useless, yet pretty objects.

As the documentary went on, I thought of the classic cynical, armchair pundit argument on the subject of art (especially concerning contemporary and conceptual art). ‘I could have made that!’, a gruff Joe Bloggs would likely grumble over his morning tea, before flicking over the page of his newspaper in disgust at some latest art exhibition— a sentiment likely countered by his classically optimistic opposite: ‘Yes, you could have, but you didn’t’. In some cases, especially as far as conceptual or other contemporary styles of art, it’s more or less feasible that the said example of art could have indeed been created by anyone (or at least an average person with basic technical or artistic skills), yet the fact is that they didn’t and the artist, well, did. However, as far as figurative art is concerned— great art that we hold in indisputably high regard due to its scale, technicality or intricacy (i.e. Cubism, Surrealism, Pre-Raphaelite, Renaissance etc), what is their actual value as unique artefacts of craftsmanship and why do we hold them in such regard if their work can be copied so well? If we see the likes of Da Vinci, Hopper, Catlin, Michaelangelo, or Picasso or Freud as genius artists, surely we can only call them thus only in acknowledgement of their artistic ideas and being the first to make these works, as opposed to for simply possessing the talent to manifest them. Is the genius in the concept, the execution, both or neither? The objective skill required in the formation of ideas, compositions, angles, references and the like perhaps goes without saying, but the talent— the rare, once-in-ten-lifetimes amount of worth, acclaim and worship that we apply to their legacies as artisans of the brush, pencil and palette knife— perhaps less so. Of course, I am just speculating— there are counter questions too, like: can a forger ever truly diminish or bring into question the artistic abilities of the original creator, if it’s merely a copy? What about similar arguments when applied to the worlds of music, or even literature? But it does make you think, especially from the angle of contemporary artists that do not physically make own artwork (i.e. Damien Hirst’s infamous spot paintings, where only twenty five out of fourteen hundred were painted by him) suggesting that said art is simply their idea, creativity and vision being manifested by another person. Could this modern outlook on art, apply to forgeries, in that anyone who has the creative ability to convincingly create work in an artist’s style and manifest an assumed creative vision on the artist’s behalf, can at very least earn themselves some sort of acknowledgement of legitimate, valuable merit? Who knows for sure.

Without spoiling the documentary’s conclusion, it ended as well as it could have, given the circumstances. Yet, when all was said and done, I couldn’t help but feel a sense of awe, not only in the twists and turns of the storyline, or in the exposé of a factory in Shenzhen in China where forgeries were being made en masse for western clients, or in seeing first-hand how the seduction of a piece of art can win people’s lives over, but in the reality that over fifty one years since his death, people are in court fighting over a work by Rothko, that never was. When researching for this essay, I found an article online that joked that perhaps Rothko had opted for such a simplistic style that could be easily copied, in order for instances regarding authenticity like this to crop up in the future— the ultimate practical joke on the art world. It’s a nice thought. The forgery in the heart of the case, despite going from being worth $8.3 million to nothing overnight (alongside thirty one others) went on to be exhibited in an exhibition in Delaware’s Witherthur Museum, entitled Treasure on Trial— existing as a hat-tip not only to the processes involved in analysing and determining inauthentic art, but also in the subjective skill of these anonymous, faceless artisans of sorts that are likely paid a minute fraction of what their works generate. A fair and fitting end to a piece of art that never was, and yet still made its place in the world, if but for a decade. And of value? Perhaps forgeries— great forgeries, so-called sublime forgeries like the one in the documentary at worst, help drive up the price of genuine art, allowing buyers and bidders to pay even greater homages to the great minds behind the works, and at worst play a fraudulent, yet necessary role in art world in tugging at the fraying strings of a opulent societal tapestry, piecing it apart bit by bit— a curious, freeing idea worth more than any anonymous eight-figure telephone auction bid.