A Time for New Dreams.

Grace Wales-Bonner

Exhibition Review

Serpentine Gallery

Written February 2019.

Image courtesy of Serpentine Gallery.

Grace Wales-Bonner was a name that up until the morning of visiting her exhibition: A Time for New Dreams at the Serpentine Gallery, I knew virtually nothing about. Having read a little about her in preparation; that she was a so-called cultural polymath, of mixed heritage and had gained a number of successes and accolades as a fashion designer by way of harnessing both her european and (more importantly in the case of her work) black identity within her works, I felt confident with the potential of seeing some work that would make my trip down to Central London from the art-deficient suburbs of North West London, worth it. Now (what I realised in much more detail, once I got home and began drafting this, was) Wales-Bonner, for her age, is fiercely successful. Although very widely documented, it’s worth reiterating that at age 23, she won the L'Oréal Professional Talent Award for her graduate collection back in 2014, became the youngest fashion designer to exhibit her work at the Victoria and Albert Museum a year later, was invited by Hans Ulrich Obrist later in the year to take part in the Serpentine Gallery’s ‘Transformation Marathon’ later that year, was awarded Breakthrough Designer at Harpers Bazaar’s Women of the Year, the following year… the list goes on, and these are merely the highlights. With a C.V so bulletproof, and a design aesthetic, philosophy and overall identity, so widely championed, expanding into other areas of creative expression would not only seems plausible but both necessary and exciting. With all of this in mind, I wanted so much to love ATFND, but I struggled, leaving feeling impressed on one hand, but... a tad let down on the other.

Image courtesy of Serpentine Gallery.

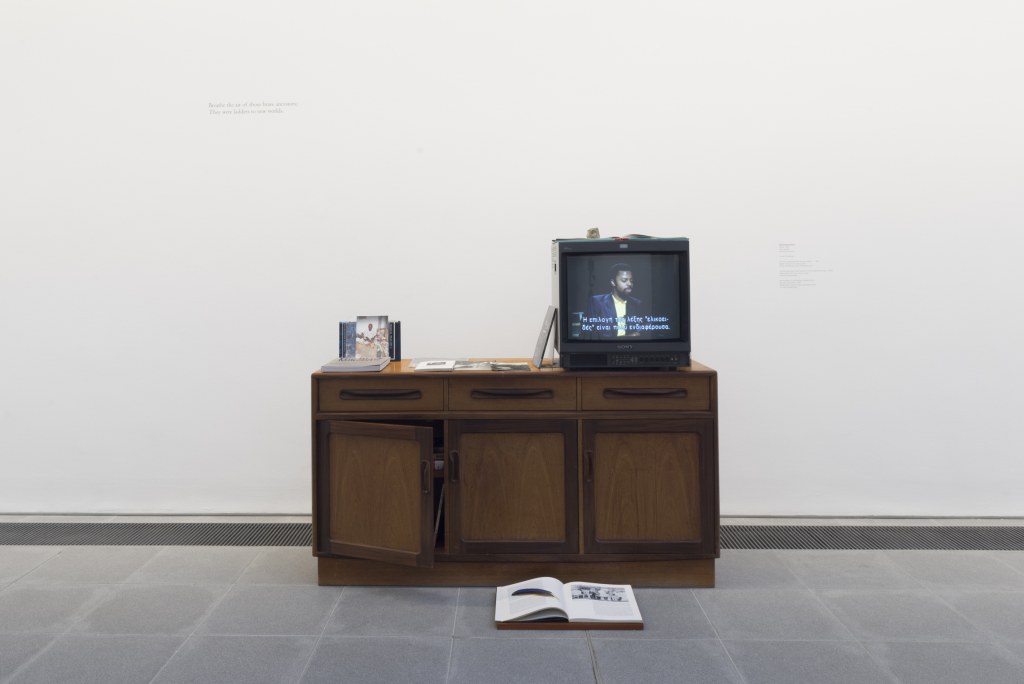

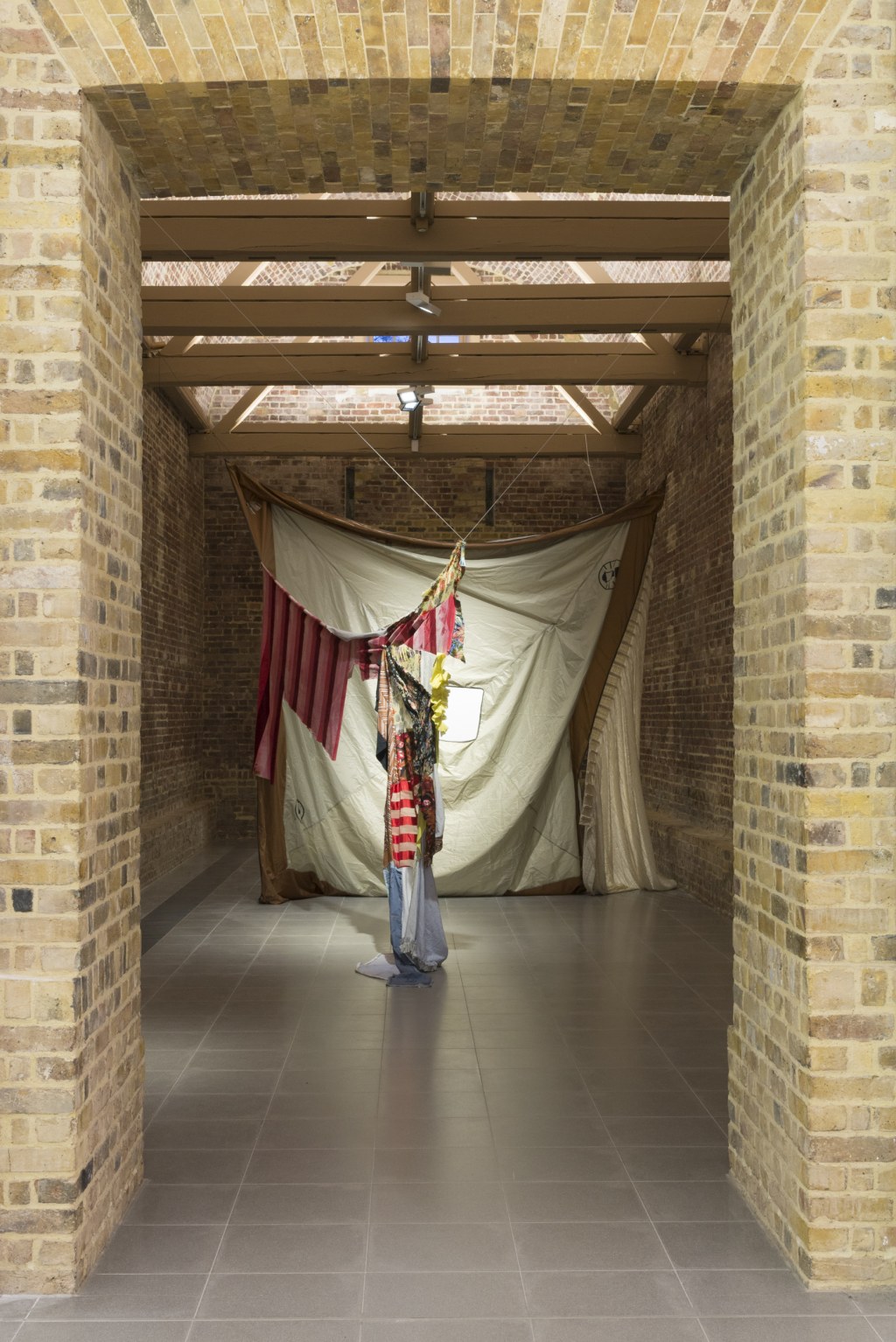

My first issue arose during my first circuit of the Serpentine: although it was Wales-Bonner’s exhibition, it transpired that only two of the pieces of work were actually by her. It was said to be curated by Claude Adjil; it wasn’t marketed as a group exhibit— this conflict threw me a bit. Maybe my confusion was down to my own ignorance, but it seemed at best, a possible oversight and at worst, a marketing ploy. That said, the variety of artists involved (Chino Amobi, Black Audio Film Collective, Rotimi Fani Kayode, David Hammons, Michael John Harper, Liz Johnson Artur, Rashid Johnson, to name but a few) meant that there was a wide array of offerings from many perspective and creative disciplines. After decoding the introductory foreword printed on the gallery wall, it became clearer that the focus overall was that both of black consciousness, by way of the concept of the shrine as a symbolic pathway, accompanied by an exploration of ritual, mysticism and more. This, was in turn inspired and accompanied by the writings of Nigerian Poet and Novelist Ben Okri, whose involvement in the exhibition by way of three visible poetic invocations commissioned for the exhibit (and displayed over several walls) was both palpable and powerful. Amongst the works themselves, stand-out examples included the work of the late Rotimi Fani Kayode, whose photographic works, rich in visual contrast, emotionally taut and deeply primal, communicated an air of frustration, identity and desire. There was a touch of humour; David Hammons’ Rock Head (2000), a piece that involved a large rock, adorned with afro hair in the form of canerows. Other references to the natural world, by way of Kapwani Kiwanga’s Flowers for Africa: Mozambique (2014) were vibrant and pleasant, as well as the cleverly constructed Fly Jar (1998) and sepia toned photograph, Money Tree (1992), both by David Hammons. Other works, interpreted the theme of shrines more literally. Multi-instrumentalist, contributed Transformations (2019): a large orange ensemble of delicate looking cloths, instruments, idols and a photo of a Hindu deity; an arrangement which was finished with the handwritten note: The highest romance is meditation. Enticing other senses, was Sahel Sounds Radio’s offering; a vintage boombox, passively playing a range of spoken word and percussive music to passers by, which did feel like a privilege to listen to. Most importantly however, there was Wales-Bonner’s installations. Shrine I. (2019) and Shrine II. (2019): two orchestrations, comprised of vintage domestic furniture items- I, with a television, surrounded by afrocentric literary titles (such as Voodoo And the Art of Haiti, The Black Monastic etc), held open on specific pages whilst II, was an arranged collection of vintage hi-fi speakers, playing a sound installation by Chino Amobi. For me, this is where the exhibition itself succeeded the most. When the breadth of Wales-Bonner’s research in accumulating these multimedia artefacts, that encompass and communicate such a focused black identity, not only as merely interesting, or even radical, but revolutionary within various historic contexts, becomes apparent, there’s no denying a real sense of painstaking, theory orientated genius. Watching an impassioned, suave Ishmael Reed speak (on subjects such as pre-western african religions surviving the slave trade etc) was a treat, engrossing and insightful that I felt hard to walk away from. Other exhibitive details, such as poetic extracts printed on the walls (Genius is black, because it works against the odds, does the impossible / If it’s too neat, don’t trust it) were a nice touch too. However, by the time I had done three laps of the exhibition, things like this began to matter less and the exhibitions two major flaws: curation and context, began to matter more.

Image courtesy of Serpentine Gallery.

Now, I saw some brilliant work; technically, artistically and otherwise. Take for instance Paul Mpagi Sepuya’s photographic offerings: beautiful colours, well exposed, solid even depth of field across all three images. But why were they there? What was I looking at, and how was it relevant to the theme? Only four pieces in the exhibit were created this year; the photographs weren’t part of this, so the possibility that they were created as a mere abstract take on the theme (something that I was secretly hoping), lacked any weight. I then began to ask the same question about Kapwani Kiwanga’s flowers that opened the exhibit, and a number of others; namely Hammons The Holy Bible: Old Testament (2002), Eric M Nack’s A Lesson in Perspective (2017), Rock Head (as mentioned earlier)... infact, apart from works that were either literal shrines (i.e. Rashid Johnson’s Untitled duo, or Liz Johnson Artur’s There is only one…one) or work that could be interpreted without too much abstraction or guesswork as a metaphorical take on the idea of a shrine (i.e. Wales-Bonner’s own contribution, as a domestic shrine?), the show seemed to be home to a lot of work that felt simply like indulgent filler. This is by no means is a critique of the standard of work: Rotimi Fani-Kayode, a photographic genius no less, was a creator of some incredibly powerful, important and brilliant photographs that shaped black sexuality and identity forever, but I’d really have to challenge anyone who’d seriously suggest that his work, or more importantly those selected, had any place within the exhibit. For me, at times it really felt as though the budget available for the show itself, combined with a potential latent desire of those involved to be doing so for association with Wales-Bonner, made for a visually impressive yet curatively questionable exhibition. Although it may seem like a pedantic cry, well informed ephemeral materials go a long way in regards to context and understanding; otherwise cool art just looks cool; good art just looks good, without any reason for its place or purpose (note: there was an exhibition guide provided, but it was useless— I later discovered that there was a beautifully designed exhibition guide available online, which would have helped the actual exhibition along, had that one been there in the flesh).

Be that as it may, what Wales-Bonner ultimately presented is a celebration; one of creed, of culture, of diversity within all that we know to be African; all that we understand to be black (even as a black artist myself). I recently saw that during her interview with the Guardian, she confessed, very honestly some of her anxieties regarding the show. ‘I’m a fashion designer, making art— it could be seen as silly’, she told Alex Rayner, and honestly I couldn’t disagree more. Her offerings of art were empowering, insightful and certainly the crown upon the head of the exhibit itself, straying aeons away from approaches exhausted and base, expressing amongst her peers across all senses and all mediums; those are indeed reasons enough to make the journey over, and see it for yourself.